The fight is picking up right where it had left off.

The fight is picking up right where it had left off.

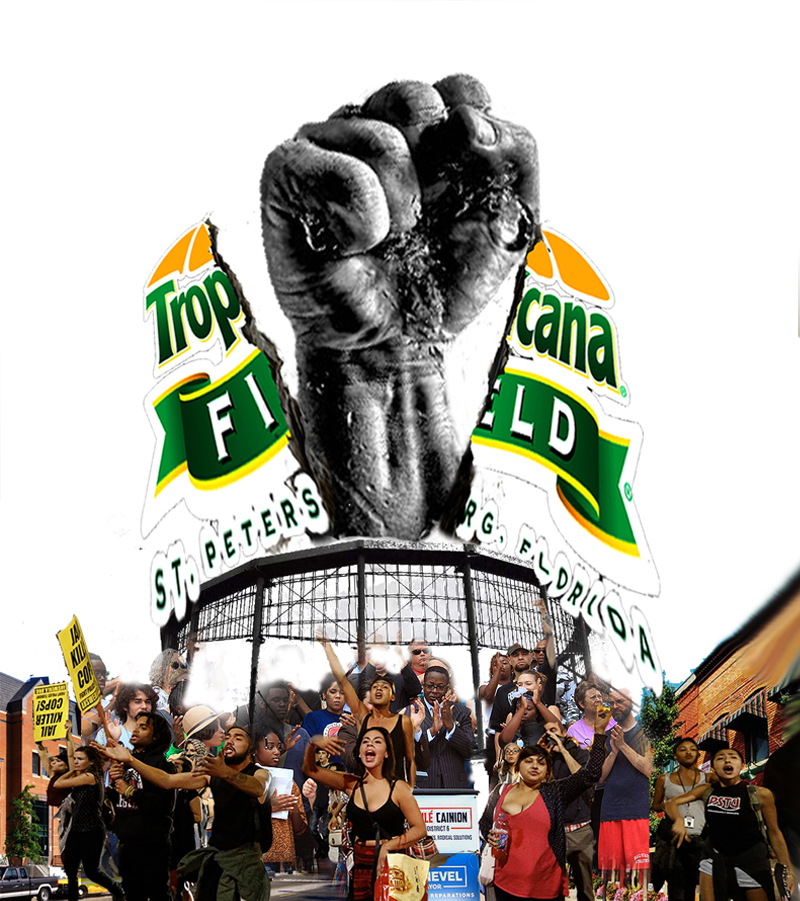

Last summer, the St. Petersburg political scene was rocked by the Uhuru-backed candidacies of Jesse Nevel for Mayor, and Akilé Cainion (now Anai) for City Council District 6. The establishment battle plan had been to stage a Kabuki dance between the “two Ricks” — Mayor Rick Kriseman and former Mayor Rick Baker — sparring over who could best manage Gentrification and the city’s war against the Black community. As the local fishwrap Tampa Bay Times reported, it was “the ugliest, and definitely the most expensive, mayoral race in modern St. Petersburg history” and “both Ricks clearly preferred to rip each other to shreds rather than offer inspirational messages.”

The “inspirational message” came from the Jesse/Akilé campaign, as the duo and their multi-racial Uhuru backers crashed the party. With supporters cheering them on (such applause was considered a serious breach of decorum), the Jesse/Akilé tandem effectively redefined the debates (it’s called “hegemony”) to focus on reparations, i.e., economic development for the Black community, Black community control of the police, and taking back the Dome —returning the Tropicana Field baseball stadium to the Southside Black community for construction of affordable housing for the Southside’s residents.

Debate sponsors, most notoriously the League of Women Voters at the Hilton brouhaha, tried to shut the people’s voices down, to no avail. By the time the end of the Primary debate season was approaching, officials were in full panic mode. For the final debate (the only one to be televised), the show was abruptly declared “by invitation only.” At the end, the July 25 snoozefest featured the two Ricks hunkered down behind locked doors guarded by a cordon of police, while “rip[ping] each other to shreds” over who was to blame for the city’s sewage scandal. That night, Jesse and Akilé directly addressed the people assembled in Williams Park on the issues that they had been fighting for since Day One.

Fast forward to August 6, 2018.

The setting was to be a Community Meeting at the Student Center of St. Pete’s University of Southern Florida. The purported intention was to gather community input to the city’s Master Plan for the 86 acres south of Central Avenue now housing Tropicana Field, the “greatest development opportunity in the Tampa Bay area.” (The Tampa Bay Rays are currently limping towards destroying a new neighborhood in Tampa.)

The setting was to be a Community Meeting at the Student Center of St. Pete’s University of Southern Florida. The purported intention was to gather community input to the city’s Master Plan for the 86 acres south of Central Avenue now housing Tropicana Field, the “greatest development opportunity in the Tampa Bay area.” (The Tampa Bay Rays are currently limping towards destroying a new neighborhood in Tampa.)

Some 15 members of Communities United for Reparations and Economic Development (CURED), including three of us who were also part of the Green Party of Florida Stop Gentrification Working Group, were on the scene, intent on again demanding that the Tropicana site be handed over to the city’s Black community for affordable housing. Already it looked bad, as police were stationed all around and inside the building.

Once indoors, we quickly learned that there was to be no direct community input whatsoever. The 200 people who showed up — mostly white, mostly middle-class — were instead treated to a 45-minute lecture (with slide show), and (we were told) everyone would later break down into issue groups, to be subjected to mini-lectures. No talking back there either, please.

Alan DeLisle, the city’s development administrator, droned on for his 45 minutes while a slideshow prepared by HKS rolled by with images of happy Black families, happy Black children, and happy Black students and workers, all interspersed with map after map and drawings of shining apartments, retail shops, and parking lots, capped by happy tourists paddling their kayaks down the to-be-restored Booker Creek. (HKS is an international firm which, as of 2015, “employs more than 1,000 people, making it one of the largest architectural firms in the United States and has completed services on structures valued in excess of $69 billion, with more than $12 billion of construction currently underway.”)

DeLisle threw one crumb to the Southside, by (again) calling the 86 acres the Gas Plant District. That name hearkened back to what the neighborhood had been called 32 years ago when the homes of over 800 mainly Black homes and 100 Black-owned businesses had been leveled to make room for the current ballpark. That name was erased along with the neighborhood, as it became the Southside. Later, the developers renamed it Midtown, rubbing into the faces of the Black community that Downtown now owned the land that we were there to demand be returned.

The Southside had already been ripped asunder by the extension of Highway I-275, which cut off the Gas Plant neighborhood from the rest of the Southside. Now DeLisle outlined how they would either move I-275 underground or cross over it with overpasses to give back to Southside residents access to the rest of the city. But as one astute observer noted, it was really to give invaders from Downtown free access to the Southside as the remains of the Black community would be driven the rest of the way out.

Enough was enough! We walked out in orderly fashion, making sure we had distributed the flyers inviting everyone to CURED’s next meeting two days later, where we would further develop CURED’s response to this total abrogation of democracy. This fight is only beginning.

Green Interlude: The “Stop Gentrification” Working Group.

At its 2018 General Membership Meeting held in Lake Worth the weekend of June 29 – July 1, the Green Party of Florida formed a statewide Working Group on Gentrification (“Stop Gentrification”). We are working to:

(1) Publicize the perils of Gentrification in its myriad forms.

(2) Participate in actions around the state which actively oppose Gentrification.

(3) Research and analyze specific local Gentrification plans, in order to lay the foundation for running candidates on an anti-Gentrification platform in 2019 and beyond. Work had already been done with an initial study of Gentrification in St. Petersburg.

That initial study published on the Pinellas County Green Party’s website, determined the following:

(1) [T]he city government’s boards and commission … were either strictly administrative bodies, or served as political plums doled out to the city’s ostensible business and community leaders, and ministers. However, one body stood out, the Development Review Commission. An unelected body appointed by the mayor and consisting of major developers. Their job was less to review, and more to promote Gentrification.

(2) St. Petersburg has a Comprehensive Plan, consisting of glowing generalities with little bearing on the real world.

(3) The city does have a plan, called the Grow Smarter Initiative, which lays out Downtown’s strategic plan of attracting business, building massive office space, becoming a tourist Mecca, and importing thousands of middle-class employees, who would be housed on the currently mostly-Black Southside. Current Southside residents would either become magically middle-class, or disappear.

(4) The creators of the Grow Smarter Initiative — working at the behest of the St. Petersburg Chamber of Commerce — have been reconstituted as the Economic Development Corporation (EDC). Per the 2018 City Budget, “[T]he long sought goal of establishing a private sector led and city supported Economic Development Corporation (EDC) was realized. … $182,000 is provided to fund our contribution to the implementation of the Grow Smarter program … $100,000 is provided to meet our financial commitment to the EDC.”

Thus the city pays the Chamber of Commerce for its EDC, which then oversees the city’s implementation of the Chamber of Commerce’s plan for gentrifying the city. The theft of the Gas Plant’s 86 acres is a key element of their plan. Pretty slick, eh?

And nowhere in all this is to be discovered the slightest shred of democratic process.

As they said in the X-Files, “The truth is out there.”

We began looking around the rest of the state. We discovered that both Palm Beach and Miami–Dade counties also have Comprehensive Plans, very similar in loftiness and emptiness to St. Pete’s

“His Master’s Voice.”

West Palm Beach and Lake Worth in Palm Beach County (each city one-tenth the size of St. Pete) have their own Comprehensive Plans. In both, the Planning & Zoning Division has responsibilities similar to St. Pete’s Development Review Commission, but with additional responsibilities as well. In West Palm Beach, it has responsibility for the implementation of the City’s Comprehensive Plan and the enforcement of the Downtown Master Plan.

The Master Plans seem to be closely tied to, if not the direct products of, private corporations. Both cities have CRA’s (Community Redevelopment Areas). [For comparison, St. Pete has four CRA’s, with the South St. Pete one being the only one of major size.] The Palm CRA’s are closely tied to private development. The CRA’s and Master Plans seem to contain the relevant information for us.

Miami–Dade (pop. 2.7 million), of course, has a Comprehensive Plan, as do the individual municipalities within the county. According to the developing pattern, Miami-Dade also publishes its planning via Master Plans, or CRA’s. Miami-Dade County has 14 CRA’s. It also has the full array of Master Plans, including a Miami Zoo Master Plan.

Naturally, there is also Gentrification planning at the state level.

“His Master’s Voice.”

Where do the Comprehensive Plans come from? According to the Florida County Government Guide:

“The State of Florida has one of the most comprehensive and progressive land use planning programs in the country. [T]he Community Planning Act was enacted by the Florida Legislature for the purposes of strengthening the existing role, processes, and powers of local governments in the establishment and implementation of comprehensive planning programs to guide and control future development. … [It includes] laws, rules, regulations, and policies affecting all planning and development activities of the state and local governments.”

“… This statute requires that all local governments adopt, maintain, and implement land use plans and development regulations for all future development actions. It also requires that all geographic areas within the state be included within the jurisdiction of a local comprehensive plan and that all development actions be consistent with the adopted plan. [emphasis added]

Master Plans abound, and do not escape statutory definition. Per 163.3164 (31):

“ ‘Master development plan’ or ‘master plan,’ for the purposes of this act and 26 U.S.C. s. 118, means a planning document that integrates plans, orders, agreements, designs, and studies to guide development.”

They must be in complete accord with the Comprehensive Plans at every level. The State of Florida itself is criss-crossed with Master Plans, for such things as highways, universities, land use, etc.

Next, the Florida Redevelopment Association tells us:

“Under Florida law (Chapter 163, Part III), local governments are able to designate areas as Community Redevelopment Areas … Since all the monies used in financing CRA activities are locally generated, CRAs are not overseen by the state, but redevelopment plans must be consistent with local government comprehensive plans. …

“There are currently over 220 Community Redevelopment Areas in the State of Florida.” [among 66 counties]

Statute 163.340: “‘Community redevelopment’ or ‘redevelopment’ … may include slum clearance and redevelopment.”

Of relevance:

“163.345 Encouragement of private enterprise.— (1) Any county or municipality, to the greatest extent it determines to be feasible in carrying out the provisions of this part, shall afford maximum opportunity, consistent with the sound needs of the county or municipality as a whole, to the rehabilitation or redevelopment of the community redevelopment area by private enterprise.”

On Democracy.

Statute 163 was duly passed by the Florida State Legislature. The millionaire legislators in Tallahassee who passed it were duly elected. So one could argue that we are seeing democracy in action. And the Florida Statute 163.3181(2) states:

Statute 163 was duly passed by the Florida State Legislature. The millionaire legislators in Tallahassee who passed it were duly elected. So one could argue that we are seeing democracy in action. And the Florida Statute 163.3181(2) states:

“Public Participation in the Planning Process … There should be provisions for notice to keep the general public informed and provisions to assure that there are opportunities for the public to provide written comments. … “[N]otice of all official actions which will regulate the use of their property … [shall be provided to] real property owners.”

So property owners get notified. The public is notified … how? Posting notices? The 200 people who showed up last week, mostly white, mostly middle-class? The only feedback allowed was to be written on the back of a form passed out to the crowd. People had a checklist of all the good things that the developers were promising. People could not as a body speak to each other. The representation of the people of the Southside came from the CURED delegation — which was effectively silenced.

The very next day, the City of St. Petersburg’s website officially reported on the Community Meeting, declaring “overwhelming” support for their checklist items. At the bottom of PowerPoint page after page, it read, “This is what we heard.” Heard? Then the city proudly announced, on the basis of this “overwhelming” community support:

“The work will build upon the outreach conducted during the preparation of the scenario and is expected to be complete by October 1, 2018.”

The law was adhered to. Again, democracy in action.

Democracy has historically had various meanings. First, there is formal democracy as written by our frankly slave-holding forefathers (or the forefathers of some of us, at least). Elections are held, representatives are chosen, and the representatives go on to allegedly represent us within the boundaries of written law, or through writing new laws. To be sure, the gains of “formal” democracy — such as they are — are precious and we defend them.

But as Greens know very well, such formal democracy is prone to control by “malefactors of great wealth” who are adept at wielding that wealth for their private ends to the public’s detriment. This is the Democracy we saw last week.

But over the years, an understanding (and practice) of democracy has developed which sees democracy as activity by the masses of people, rather than merely a set of rules. “Participatory democracy,” as it was called in the 60’s.

So the Monday debacle adhered to the statute, but bore no resemblance to democracy as Greens understand it. Yes, we were allowed to submit written comments at the end. But nobody could speak. Thus people were not allowed to address each other, but only address (in writing) those who had already determined what the questions could be.

The Economic Deep State.

It wasn’t so long ago that anyone talking about the “Deep State” — an invisible permanent and unaccountable government that ruled the U.S. from behind the scenes — was dismissed as some kind of conspiracy nut. Tinfoil hats and all that. Then Trump got elected president with a foreign policy agenda that was utterly imperialistic, but differed in detail from the ascendant neocon pursuit of “full spectrum dominance.”

Out of the shadows, the Deep State charged forth, trumpeting full spectrum anti-Russian hysteria with the disturbing complicity of the Beltway liberal AND conservative establishments. Liberals of every stripe, and too many even on the Left, went full throttle complicit while MSNBC sang the chorus. Every move Trump made to defuse belligerence against Russia, any moves to draw down U.S. intervention in Syria or Afghanistan or Korea, were sabotaged by operatives in the U.S. intelligence agencies, the State Department, and the military, which began conducting their own belligerent foreign policy lest peace threaten to break out.

Deep State has now become part of the modern American vocabulary, i.e., a permanent government unfettered by Democrats or Republicans, unelected but setting policy unfazed by any democratic (small “d”) checks or balances.

Stripping last week’s Community dog-and-pony show to its bones, what we saw was CURED — the community-being-born — confronting the Economic Deep State of the State of Florida. Democracy as an activity in action.

Take it to the South Side and beyond.

On August 8, CURED reconvened at Akwaaba Hall, unfazed by Monday’s rebuff, to further develop how to Take Back the Dome. Monday was reviewed. Responsibilities were assigned. It was clear that the city and the developers were afraid, very afraid, just as it was revealed by that last debate of the 2017 mayoral primary being held behind closed doors. Various measures are now being considered to take the 86 acres and turn them into affordable housing for the dispossessed Black community. Come what may, CURED will be hitting the streets this fall, organizing to Take Back the Dome, and building a long-term precinct operation in the process. Last week we had gone into what the developers had thought was their “home” territory and they had gotten the message.

At the August 8 meeting that we had publicized, several new people joined us. But one of them seemed very out of place. We went around the room to introduce ourselves. This tall white guy, dressed in “rich guy on casual day” attire, said his name was Buddy, that he was a developer from Chicago. Looking to “listen and learn and love.”

Coming in the door, Buddy had shaken hands with two women in CURED. Not friendly handshakes at all. Deliberately and painfully bone-crushing. Menacing. A challenge and a threat.

During that meeting, one of the women looked him in the eye, said, “The developers’ plans and schemes aren’t going to happen. They need to throw them away.” Another member related how incredibly expensive executing their Master Plan would be, the enormous risk they were running in trying to make good on their investments, what outrage they would provoke. By creating a “hostile development environment,” we could cost them billions. Buddy walked out.

We had challenged them on their home ground on Monday. They walked into ours two days later. We get the message. The battle for the Dome is on.

— Jeff Roby

August 16, 2018